In relationships with people, zero-sum games are dangerous. That's when one person's gain means another's loss.

I remember, at the beginning of the war, I had to spend the night at the central train station in Kyiv. Everyone tried to avoid sleeping on the cold, hard floor. Everyone tried to avoid sleeping on the cold, hard floor. When the couches were occupied, conflicts over tables began.

Limited resources bring out the worst in people.

What will you do? It's better not to tempt yourself.

Knowing this, it makes sense to avoid antagonistic games as much as possible.But what if fate throws you into one?

There are a few options:

1. You can observe what's happening as a social experiment. Your understanding of people and yourself will deepen significantly.

2. It's better to expand the boundaries of the zero-sum game. Humor helps. About 30 years ago, we got stuck on a cable car in Crimea. It was hot, crowded, children were crying, and, of course, there were quarrels. Someone got yelled at, and his friend whined, "It's his birthday today!" Everyone burst out laughing and then suddenly started singing in chorus: "Happy Birthday to you." Peace immediately prevailed.

3. Or you can take a philosophical approach, thinking that there is a time for fight and aggression, and a time for acceptance and love. Gregory David Roberts described this well in his novel "Shantaram":

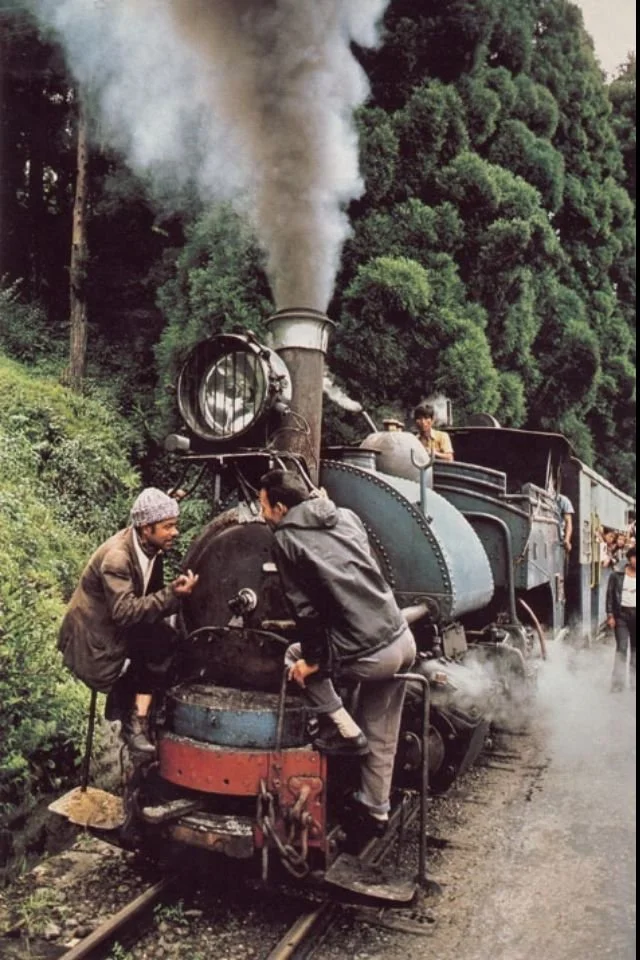

"But as soon as the train departs and fighting for seats is no longer a necessity, the passengers become friendly and courteous.

A man opposite me shifted his feet, accidentally brushing his foot against mine. It was a gentle touch, barely noticeable, but the man immediately reached out to touch my knee and then his own chest with the fingertips of his right hand, in the Indian gesture of apology for an unintended offence. In the carriage and the corridor beyond, the other passengers were similarly respectful, sharing, and solicitous with one another.

At first, on that first journey out of the city into India, I found such sudden politeness infuriating after the violent scramble to board the train. It seemed hypocritical for them to show such deferential concern over a nudge with a foot when, minutes before, they'd all but pushed one another out of the windows.

Now, long years and many journeys after that first ride on a crowded rural train, I know that the scrambled fighting and courteous deference were both expressions of the one philosophy: the doctrine of necessity. The amount of force and violence necessary to board the train, for example, was no less and no more than the amount of politeness and consideration necessary to ensure that the cramped journey was as pleasant as possible afterwards. What is necessary! That was the unspoken but implied and unavoidable question everywhere in India.

When I understood that, a great many of the characteristically perplexing aspects of public life became comprehensible: from the acceptance of sprawling slums by city authorities, to the freedom that cows had to roam at random in the midst of traffic; from the toleration of beggars on the streets, to the concatenate complexity of the bureaucracies; and from the gorgeous, unashamed escapism of Bollywood movies, to the accommodation of hundreds of thousands of refugees from Tibet, Iran, Afghanistan, Africa, and Bangladesh, in a country that was already too crowded with sorrows and needs of its own. The real hypocrisy, I came to realise, was in the eyes and minds and criticisms of those who came from lands of plenty, where none had to fight for a seat on a train."

Sincerely yours,

-Alexander