At such moments, the business leader is forced to admit that his own experience and intellectual power in a particular area are not enough and must seek support from outside. So, naturally, the entrepreneur finds an expert in a field that is relevant to him - for example, in attracting private investment, marketing, or launching a business in the Asian markets. Through trial and error, the manager selects an advisor whom he can trust, both as an expert and as a person. As long as the cooperation brings tangible benefits to the business, it continues, but if it has run out, the entrepreneur stops it.

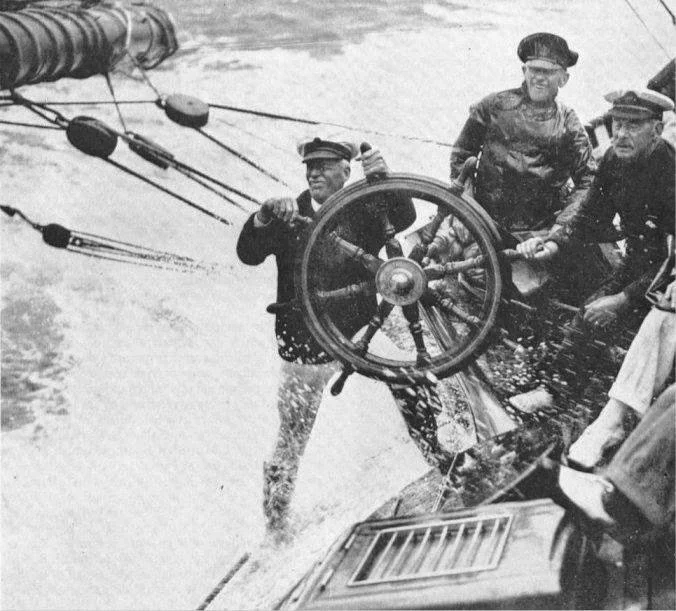

Over time, the manager develops a circle of reliable external advisors in different areas, with each of whom he successfully interacts individually. One day the manager decides to bring these specialists together, for example, to discuss his particularly confusing problem. By listening to the opinions of different advisors at the same time, the entrepreneur significantly improves his understanding of the crisis situation and his options for getting out of it. This is similar to the echolocation of a bat, which navigates in total darkness using ultrasound reflected from other objects. Having seen from personal experience the usefulness of such a discussion, the next logical step for a manager is to call such a meeting an Advisory Board and hold it either regularly or as worthy problems arise. That is how the Advisory Board, the next stage in the evolution of corporate governance, is born, naturally before our eyes.

This format can last for years and benefit the founder of the business, who serves as the CEO. As before, he alone makes all decisions, but their quality increases at the expense of outsourcing the experience, knowledge and process capacity of other people. Once the CEO comes to the conclusion that he fully trusts the opinion of the Advisory Board members and wants to increase their involvement in his business. It may also be time to hire an outside professional as CEO, as the business owner wants to move away from operations and focus on vision and strategy building. The logical next step in the evolution is to turn the Advisory Board into a full Board of Directors, which will include trusted advisors as non-executive or independent directors and maybe someone from the top management (an insider or executive director), such as a CFO.

The difference is that now the founder of the business ceases to make all key decisions unilaterally and delegates some powers to the Board of Directors as a collegial body, in which he, for example, takes the role of Chairman. Now each of the directors not only recommends this or that decision, as he did before, but also bears responsibility for his mistakes. As a result, the quality of decisions is taken to new heights, which means more profits and increased business value for the owner. It is important that the transformation of the highest authority from sole authority to collegiate authority occurs gradually and organically, allowing the founder to retain control of the business at all stages. By sharing power with others, in return he acquires something more - expansion of the most limited resource in the company - himself.

So we see that the business has got the same three-tier corporate governance structure (CEO, Board, Shareholders), which, however, has grown from the bottom up. It is important to note that the main driver of the bottom-up process is improving the quality of the leader's decisions, as opposed to the top-down process where the driver of the process was control. To summarize, the point of corporate governance is to: 1) guide the company, 2) control, and 3) improve the quality of key decisions.

If the entrepreneur has not understood the origins, functions and evolution of corporate governance, there may be polar attitudes about it. In the first case, the fear of losing control over the business forces the owner to avoid any practices of corporate management, and thus to limit the quality of his strategic decisions. Then, in the best case, business growth rates slow down, competitive advantage weakens, market share is lost, talented employees leave and windows of new opportunities close. There is nothing to say about the worst case.

In the second case, corporate management is perceived as a tribute to fashion "like others" or even as a religious revelation which must be ritually implemented in your company. The owner creates a Board of Directors, but he does it formally, as if he is trying to wear a suit he has chosen at random. The result is a stillborn Board which does not fulfill any of its functions. Errors in evaluating the expertise and complementarity of participants, the lack of independent directors, the unclear distribution of powers, meaningless bureaucracy, and decision-making outside the meeting - these and many other reasons make this initiative profane. Such examples generate cynicism and skepticism on the part of all observers of corporate governance in general and discredit this extremely useful tool.

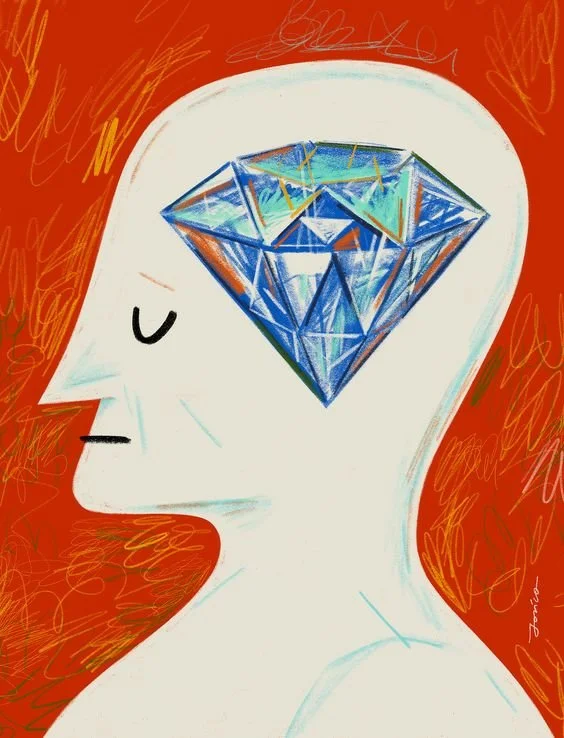

Over the past 25 years I have been in various roles - as an employee, CEO of a business, an investor, a member of the Board of Directors and the Advisory Board in various companies. I have been lucky enough to observe the work of talented entrepreneurs and learn from experienced professors at Chicago Booth and Harvard Business Schools, as well as at the UCGA. I had to assemble my understanding of corporate governance gradually, like a picture out of many puzzles chaotically scattered on the floor. I really wish someone had told me in plain language how it all worked ten years ago, or better yet, twenty years ago. I hope this article will help some of the readers save time and guard against mistakes by using corporate governance in a way that is useful and meaningful.

Sincerely yours,

-Alexander