An answer in plain language that would have helped me greatly years ago.

When it comes to corporate governance among entrepreneurs and top managers, one can often observe a reaction of confusion, awe or skepticism. Some are simply confused by the variety of new terms, concepts and practices. Others dogmatically believe that they have found the solution to all problems and expect success as a result of formally performing the rituals of the new religion. Still others, observing the behavior of the rest, scornfully ridicule the next fashionable craze that produces ambiguous results. More and more words are spoken, articles published, and speeches made on the subject. But very few people try to explain the functional sense of corporate governance as intelligible as in the annotations to the medicines or instructions to the household tools.

The reason for a negative or distorted perception of corporate governance is partly because the subject area itself has not matured yet and even among specialists you can find different definitions of basic terms. The philosopher Thomas Kuhn divided the sciences according to the degree of paradigm development. He believed that the more the scientific community agreed on terminology, concepts, techniques, and values, the more rapidly a given science developed. Thus, by agreeing on fundamental concepts, people focus on solving increasingly complex problems, rather than arguing endlessly with each other. In this sense, physics and mathematics are at one end of the spectrum, while sociology and psychology are at the other. The paradigm of corporate governance is also still underdeveloped, although formally born several centuries ago.

The word Corporate comes from the Latin Corpus, meaning the human body, and the word Governance comes from the ancient Greek Kubernaein, meaning the art of steering a ship. Moreover, the skipper, that is, the captain of a sailing ship, is not just a beautiful metaphor. Modern corporate governance has its roots in the sixteenth-seventeenth century, when the young Dutch Republic gained independence from the Spanish Empire in a struggle and became the first bourgeois state in Europe. Within a short period of time, the Republic achieved such significant advances in trade, science, and the arts that this period has been called the Golden Age of the Netherlands. This was aided on the one hand by the protection of property rights and a stable system of taxation, and on the other by freedom of faith, enterprise, learning, and citizenship. The economy of the Republic grew at an unprecedented rate from maritime trade and the wealth of colonial possessions in Asia.

The essence of corporate governance becomes clear with the example of the Dutch East India Company (1602-1798), which was the world's first stock firm and was so powerful that it would be worth approximately $7.9 trillion today. The company's owners provided the capital and assumed the financial risks, for in those dashing times only one ship in three would return home. However, the fabulous profits from the trade in tea, spices, opium, and silk justified these uncertainties.

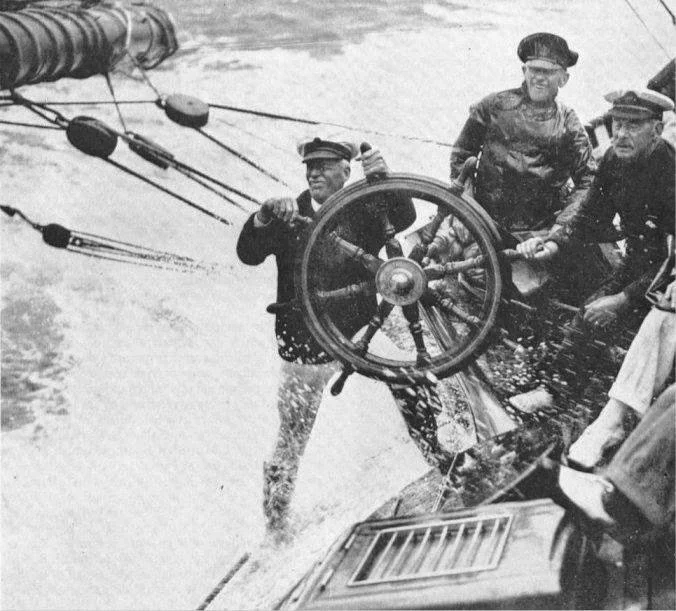

Return of the second Asia expedition of Jacob van Neck in 1599 by Cornelis Vroom

The captain of the ship hired the crew and contractors and was in fact the CEO of the business project - an adventurous expedition to a faraway land. As a result of the separation of ownership and control, there was inevitably a conflict of interest, which economists call the principal-agent problem. Although the stated purpose of the project was to preserve and increase shareholder capital, each member of the team also had his own self-interest. There was also inevitable asymmetry in information, making investors nervous as control of the project literally slipped from their grasp.

So there was a natural need for independent directors, whom the owners appointed to look after the project on their behalf. As a rule, two directors were sent on a voyage, one controlling the actions of the captain, and the second to monitor the purity of the first, according to the two-man rule. In fact, this basic management structure (owners, directors and the captain) is still in place today, because despite all the breakthrough technological innovations, human nature has not changed significantly, nor has the conflict between the interests of the customer and the contractor disappeared.

Today, the role of the captain of the company is played by a hired CEO and his team. Above the CEO, there is the Board of Directors, which has at least a control function. Above him is the General Stockholders' Meeting, the highest body in a joint-stock company, which is made up of the owners of the corporate rights. This is the so-called corporate governance triangle, typical of the Anglo-American model of corporate governance (I am not discussing here the Japanese and German models in order not to complicate things). The General Meeting of Shareholders appoints the members to the Board of Directors. The Board of Directors appoints and dismisses the CEO. Everything is simple and logical. Here is an apt definition from the architect of corporate governance reform, Sir Adrian Cadbury: "Corporate governance is a system by which a company can be controlled and directed."

Source: BTS Group

It was a top-down view of the corporate governance function, from investors to the captain. This is often the view that is limited to this. But there is another useful perspective, from the bottom up. Imagine you are the founder of a new business. For the first few years, while your company searches and polishes its business model, you have to make all decisions alone. That freedom may be inspiring to some, but a mature entrepreneur knows how agonizing the downside is with the responsibility for making the wrong decisions. A leader has to figure everything out on his own, being constantly under severe stress from the fact that the level of complexity of problems exceeds his level of competence. It seems that nobody can help the founder - his wife and friends do not understand the subtleties of business, the employees do not think so broadly, and it is scary and probably expensive to turn to experts from outside.

If the business survived and got back on its feet, it is likely that either the number of mistakes made was small, the market forgave everything, or competitors made mistakes much more often. Sooner or later, however, there comes a point when the founder of a company encounters abnormal events that threaten to destroy his entire business. In a remarkable article that has become a classic, Neil C. Churchill identifies five stages of small business development, which means the inevitable encounter with crises - leadership, autonomy, control, bureaucracy, etc. And although, the solutions for them are already known - growth through creativity, direction, delegation, coordination and cooperation, translating these ideas into reality is by no means a trivial exercise. In addition, crises also occur for other reasons - the entry of a global competitor into the market, the obsolescence of the current business model, changes in legislation, founder burnout, conflict between shareholders, and so on. As a result of such events, the founder, and then the entire company, plunge into chaos for a while.

Source: The Five Stages of Small Business Growth by Neil C. Churchill and Virginia L. Lewis, HBR

At such moments, the business leader is forced to admit that his own experience and intellectual power in a particular area are not enough and must seek support from outside. So, naturally, the entrepreneur finds an expert in a field that is relevant to him - for example, in attracting private investment, marketing, or launching a business in the Asian markets. Through trial and error, the manager selects an advisor whom he can trust, both as an expert and as a person. As long as the cooperation brings tangible benefits to the business, it continues, but if it has run out, the entrepreneur stops it.

Over time, the manager develops a circle of reliable external advisors in different areas, with each of whom he successfully interacts individually. One day the manager decides to bring these specialists together, for example, to discuss his particularly confusing problem. By listening to the opinions of different advisors at the same time, the entrepreneur significantly improves his understanding of the crisis situation and his options for getting out of it. This is similar to the echolocation of a bat, which navigates in total darkness using ultrasound reflected from other objects. Having seen from personal experience the usefulness of such a discussion, the next logical step for a manager is to call such a meeting an Advisory Board and hold it either regularly or as worthy problems arise. That is how the Advisory Board, the next stage in the evolution of corporate governance, is born, naturally before our eyes.

This format can last for years and benefit the founder of the business, who serves as the CEO. As before, he alone makes all decisions, but their quality increases at the expense of outsourcing the experience, knowledge and process capacity of other people. Once the CEO comes to the conclusion that he fully trusts the opinion of the Advisory Board members and wants to increase their involvement in his business. It may also be time to hire an outside professional as CEO, as the business owner wants to move away from operations and focus on vision and strategy building. The logical next step in the evolution is to turn the Advisory Board into a full Board of Directors, which will include trusted advisors as non-executive or independent directors and maybe someone from the top management (an insider or executive director), such as a CFO.

The difference is that now the founder of the business ceases to make all key decisions unilaterally and delegates some powers to the Board of Directors as a collegial body, in which he, for example, takes the role of Chairman. Now each of the directors not only recommends this or that decision, as he did before, but also bears responsibility for his mistakes. As a result, the quality of decisions is taken to new heights, which means more profits and increased business value for the owner. It is important that the transformation of the highest authority from sole authority to collegiate authority occurs gradually and organically, allowing the founder to retain control of the business at all stages. By sharing power with others, in return he acquires something more - expansion of the most limited resource in the company - himself.

So we see that the business has got the same three-tier corporate governance structure (CEO, Board, Shareholders), which, however, has grown from the bottom up. It is important to note that the main driver of the bottom-up process is improving the quality of the leader's decisions, as opposed to the top-down process where the driver of the process was control. To summarize, the point of corporate governance is to: 1) guide the company, 2) control, and 3) improve the quality of key decisions.

If the entrepreneur has not understood the origins, functions and evolution of corporate governance, there may be polar attitudes about it. In the first case, the fear of losing control over the business forces the owner to avoid any practices of corporate management, and thus to limit the quality of his strategic decisions. Then, in the best case, business growth rates slow down, competitive advantage weakens, market share is lost, talented employees leave and windows of new opportunities close. There is nothing to say about the worst case.

In the second case, corporate management is perceived as a tribute to fashion "like others" or even as a religious revelation which must be ritually implemented in your company. The owner creates a Board of Directors, but he does it formally, as if he is trying to wear a suit he has chosen at random. The result is a stillborn Board which does not fulfill any of its functions. Errors in evaluating the expertise and complementarity of participants, the lack of independent directors, the unclear distribution of powers, meaningless bureaucracy, and decision-making outside the meeting - these and many other reasons make this initiative profane. Such examples generate cynicism and skepticism on the part of all observers of corporate governance in general and discredit this extremely useful tool.

Over the past 25 years I have been in various roles - as an employee, CEO of a business, an investor, a member of the Board of Directors and the Advisory Board in various companies. I have been lucky enough to observe the work of talented entrepreneurs and learn from experienced professors at Chicago Booth and Harvard Business Schools, as well as at the UCGA. I had to assemble my understanding of corporate governance gradually, like a picture out of many puzzles chaotically scattered on the floor. I really wish someone had told me in plain language how it all worked ten years ago, or better yet, twenty years ago. I hope this article will help some of the readers save time and guard against mistakes by using corporate governance in a way that is useful and meaningful.

Sincerely yours,

-Alexander

You can help Ukraine defend itself and the World from Russian aggression here.

”Who are you and what do you do?"

As a business therapist, I help tech founders quickly solve dilemmas at the intersection of business and personality, and boost company value as a result.

"I have an important business decision to make. Can you help me?

Reserve a time on my calendar that is convenient for you to meet with me. We'll clarify your request and discuss options for how you can help.