Some stories, though simple, have deep meaning and symbolism. They come to mind again and again in different situations. One of my favorites is about catching wild monkeys in India (see the video from 1912).

A jug is tied to a tree and coveted treats for these primates are placed in it. Attracted by the smell, an animal sticks its paw inside the jug, grabs the food, but can’t get it out anymore. The throat of the jug is wide enough for your palm to fit, but too narrow for a fist to get stuck. The monkey is in a trap, of which it is a part. Seeing the hunters approaching, the monkey screams and tries desperately to pull its paw out. But it cannot simply unclench its hand and lose the treat — that’s above its bend. The pleasure is so close that even the threat of death won’t make the monkey leave it.

The pleasure is so close that even the threat of death won’t make the monkey leave it.

Inside each of us lives such a monkey, which is regularly tempted by delicious offers, deals, promises, and paws into one “jug” after another. And it doesn’t matter whether we are talking about negotiating the hiring of a valuable employee with compensation of a hundred thousand dollars, the sale of our share in a business worth ten million dollars, or a merger deal worth a billion dollars. The essence of negotiations with your opponent, and, more importantly, of internal negotiations with yourself, is the same — it is determined by the answer to the question “What are you willing to sacrifice once you get into a trap?”

Usually in a crisis, in a stalemate situation, our first impulse is to find and blame the villain who made the trap for us. This is the psychology of an unfortunate victim hunted by a hostile outside world. But if we imagine ourselves in the monkey’s shoes, we won’t any longer be able to deny our responsibility for what has happened to us.

The threat of real or symbolic death exacerbates to the utmost the problem of choosing priorities. We have to decide what is truly valuable to us and what is not. To lose “everything” but to save life in return? Or to cling tightly to an adored object, hoping to squeak through by a wonder?

I remember when I was the CEO of a business, one of the hardest moments for me was the departure of some talented employee. Feeling incapable of accepting it, I took titanic efforts to dissuade him/her out of that “mistake”. Looking back at the past, I realize the absurdity of my attempts, as the Buddhists say, to attach legs to a drawn snake (画蛇添足), i.e., to do a completely useless thing. If you and your employee are out of the way, no persuasion and bonuses will fix it. And they only weaken the position of the leader and make the inevitable breakup even more painful.

As for hunters and predators, the irony is that they are not that dangerous. Our worst enemy is ourselves. Why? We try to appropriate for ourselves what does not yet belong to us. In the pursuit of fleeting pleasure, we miss the basic meaning. We confuse the desirable with the necessary and the imaginary with the real. In other words, all this drama is made up, staged and played out in our heads.

The good news is that, as the author of the drama, we are in the perfect position to stop it. There is only one sure way: we must interrupt our pleasure. In order to do that, we will have to part with something very precious. After all, the gods will accept only a generous sacrifice. Metaphorically, it is necessary to chew off one’s paw caught in a trap. As a rule, it is necessary to part with one of the manifestations of pride. That is, an unjustifiably high opinion of oneself, one’s abilities and one’s rights.

There is only one sure way: we must interrupt our pleasure.

Buddhists consider pride to be the poison of the mind. In Orthodoxy and in Islam, pride is the most grievous sin, giving rise to all the others. In the ancient tradition, such impudent behavior is regarded as a challenge to the gods and usually leads to the sudden disappearance of good fortune, and later to divine retribution.

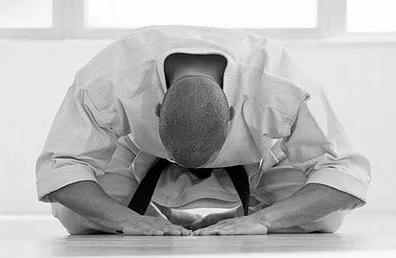

The opposite of pride is humility, that is, a sober vision of self. Humility makes it easier to free yourself from all excess by taming exorbitant passion. As a result, your decisions as a business owner, CEO or investor gain insight, foresight and irreducibility. Why? Reality is a frightening force. Now it’s on your side.

Yours sincerely,

-Alexander